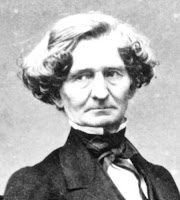

A couple years ago, we of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus sang the marvelous 8 Scenes from Faust by Hector Berlioz. This year - this week, in fact - we are performing his "dramatic legend" The Damnation of Faust. Later on I'll post a general review of the latter. For now, I only want to write about the difference between these two closely related pieces.

A couple years ago, we of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus sang the marvelous 8 Scenes from Faust by Hector Berlioz. This year - this week, in fact - we are performing his "dramatic legend" The Damnation of Faust. Later on I'll post a general review of the latter. For now, I only want to write about the difference between these two closely related pieces.The 8 Scenes is a youthful work, composed in the heat of inspiration when the 25-year-old Berlioz had just discovered a French translation of Goethe's masterpiece. It was published at the composer's own expense as his Opus 1, and eventually reworked into the larger, more mature work some 20 years later.

We are very fortunate that Berlioz's attempts to suppress his first opus did not succeed. Not only in comparison with The Damnation of Faust but also on its own terms, it is a piece worth knowing. 8 Scenes is a flawed masterpiece, marked to be sure by its composer's immaturity and impetuosity (perhaps even coarseness), but also stamped with genius. Indeed, in its brash energy and immediate inspiration, one may prefer certain points in the 8 Scenes to their counterparts in the more mature and dramatically integrated Damnation. Berlioz gave with one hand, but often took away with the other.

Some of the pieces from 8 Scenes were imported directly into Damnation with hardly any alteration. For example, No. 4, Brander's song about the rat, shows up in the Auerbachskeller scene where Mephisto introduces Faust to the pleasures of drunken revelry. Berlioz keeps the same quirky melody and the same refrain for the men's chorus. He only adds a mock-solemn "Requiescat in pace" as a final touch, and integrates it into the surrounding scene.

Some of the pieces from 8 Scenes were imported directly into Damnation with hardly any alteration. For example, No. 4, Brander's song about the rat, shows up in the Auerbachskeller scene where Mephisto introduces Faust to the pleasures of drunken revelry. Berlioz keeps the same quirky melody and the same refrain for the men's chorus. He only adds a mock-solemn "Requiescat in pace" as a final touch, and integrates it into the surrounding scene.Likewise, he faithfully transmits No. 5, Faust's song about the flea, only changing Faust from a tenor to a baritone. This is actually a very significant change, and I'm not talking merely about the tone-color of the solo voice. Among the most striking touches in the 8 Scenes was the casting of Mephistopheles as a tenor rather than a bass/baritone. In Damnation he reverts to the conventional casting of this role. One might say this change was necessary to make the larger work hold together dramatically. But one might also see in it the touch of a maturer and thus also more conservative hand. Is this an instance of the older Berlioz correcting an error of his younger self? Perhaps. But in correcting many such "errors," he may also have bled the work of some of its originality and vibrancy. Plus, in my recording of The Damnation of Faust, baritone José van Dam opts to sing a lower melody on the fifth line of each stanza ("Cruelle politique!" in the last verse), rather than the more difficult but also more memorable high road. Making Mephisto a baritone came at a cost.

Another case in point: No. 2 of the 8 Scenes, the peasants' song and dance. Originally scored for a mezzo-soprano soloist, joined by the choir at the end of each verse for an explosion of mirth ("Ha! Ha! Ha! Landerira"), it reaches its final form in Scene 2 of The Damnation of Faust as a purely choral piece interspersed with comments by Faust. In working this number into his dramatic scheme, Berlioz really trashed it. First, he pulled the stanzas apart and stuffed the spaces between them with an unrelated, and in my opinion uninspired, peasant dance idea ("Tra, la, la! Ho, ho!"). Then he actually changed what had been an exquisite melody, lowering its effectiveness.

Another case in point: No. 2 of the 8 Scenes, the peasants' song and dance. Originally scored for a mezzo-soprano soloist, joined by the choir at the end of each verse for an explosion of mirth ("Ha! Ha! Ha! Landerira"), it reaches its final form in Scene 2 of The Damnation of Faust as a purely choral piece interspersed with comments by Faust. In working this number into his dramatic scheme, Berlioz really trashed it. First, he pulled the stanzas apart and stuffed the spaces between them with an unrelated, and in my opinion uninspired, peasant dance idea ("Tra, la, la! Ho, ho!"). Then he actually changed what had been an exquisite melody, lowering its effectiveness.In the 8 Scenes version of this tune, the third line of each stanza is sung to a musical phrase that effortlessly combines asymmetry with a sense of careless rightness, and the melody of the fourth line highlights the rhythmic drive of the tune. In Damnation, the third line of the text is set, instead, to a longer and more balanced phrase that seems more mannered and less organically connected to the tune; while the fourth phrase exchanges its headlong directness and its punchy rhythm for a calmer phrase, repeated twice, in which the peasants seem to flourish their skirts. To my ear this is definitely a case of an older and more conservative composer rounding off the corners of a youthful piece, a piece that had been better left alone.

The Easter Hymn (No. 1 in 8 Scenes, Scene 4 in Damnation) also suffers, arguably, from the composer's second thoughts. In most details the two versions are identical. However, when the women's chorus joins the men for the second iteration of their hymn, the difference becomes clear. The mixed chorus writing in The Damnation of Faust is delicate and lovely, but tame when compared to the scrapped, earlier version. The women's voices merely form a part of the steadily moving choral texture in the later work, whereas in the 8 Scenes they contributed glowing cascades of notes,

like strewn flower petals floating to the ground before the feet of an ecstatic religious procession. To know that sound is to love it, is to miss it when the elder Berlioz replaces it with a more modest (albeit exquisite) evocation of Gothic architecture.

like strewn flower petals floating to the ground before the feet of an ecstatic religious procession. To know that sound is to love it, is to miss it when the elder Berlioz replaces it with a more modest (albeit exquisite) evocation of Gothic architecture.Marguerite's two numbers from the 8 Scenes - No. 6's ballad of the King of Thule and No. 7's desperate romance - seem to have crossed over to Damnation without much change. It is hard to imagine how Berlioz could have improved pieces of which one of my friends in the Symphony Chorus said something like, "I'm often torn as to whether Berlioz was a genius or a charlatan, but after hearing these pieces I would forgive him anything."

No. 7, however, ends with the remarkable chorus of soldiers, accompanied by brass and drum signals and scored to sound like they marched up from the distance and faded out of earshot again. In the Damnation, this soldiers' chorus is split into two pieces. In the first instance, the soldiers sing their entire chorus without any hint of fading in or out, and without the brass-and-drum signals that made such an impressive accompaniment in the 8 Scenes. Then, in a tour-de-force of Berlioz's specialty of combining two melodies contrapuntally, the soldiers are joined by a crowd of university students singing a bawdy alma mater ("Iam nox stellata"). After introducing both songs separately, Berlioz combines them and brings them to a glorious finish.

Much later, both the soldiers' and the students' songs come in for a reprise at the end of Marguerite's romance. This time we do hear the brass and drums, and the marching singers do seem to fade away in the distance, while the heroine breathes a sigh of despair on realizing that Faust will not come to her. Here Berlioz achieves the fade-out effect more quickly and economically than in his first essay. But the price, for those of us who know and love the 8 Scenes, is the loss of the original setting of the soldiers' song with brass-and-drum accompaniment throughout.

Much later, both the soldiers' and the students' songs come in for a reprise at the end of Marguerite's romance. This time we do hear the brass and drums, and the marching singers do seem to fade away in the distance, while the heroine breathes a sigh of despair on realizing that Faust will not come to her. Here Berlioz achieves the fade-out effect more quickly and economically than in his first essay. But the price, for those of us who know and love the 8 Scenes, is the loss of the original setting of the soldiers' song with brass-and-drum accompaniment throughout.No. 8 of 8 Scenes is perhaps an artifact of Berlioz's youthful vigor at its most awkward. Mephisto's serenade is a gorgeous melody showcasing the full range of the tenor's voice, and it really sounds nice when accompanied by nothing but a solo guitar. But as a conclusion to the 8 Scenes it is undeniably anticlimactic; so much so that, when the SLSO performed it under Pinchas Steinberg a few years ago, we moved it up ahead of No. 7. Though one hearing the guitar version might wish in one's heart to hear an orchestral setting of the serenade, the fulfillment of that wish in The Damnation of Faust comes, again, at a cost. Having changed Mephisto from a tenor to a baritone, Berlioz replaces the guitar with pizzicato strings and woodwind flourishes; he even adds parts for the men's chorus. All these touches are nice in their way, but in transposing the piece downward Berlioz also sacrifices some of the yearning intensity of the tenor version.

Finally, there is the sextet of sylphs, No. 3 in 8 Scenes from Faust and part of Scene 7 in The Damnation of Faust. Which version is better? This case is a split decision if there ever was one. The 8 Scenes version is scored for six soloists taken from the chorus; the chorus itself, or at least a semichorus, is to sing the final version. By using the full chorus, the elder Berlioz risked sacrificing some of the clarity of articulation demanded by this fiendishly tricky piece; but it was arguably a worthwhile risk, since the chorus is better able to invest the whispery iterations of "De sites ravissants," etc., with a soothing murmur and a suggestion of insect-like buzzing. Plus, in rewriting the sextet, the more mature composer brought greater economy to bear. The piece becomes more tightly constructed, clocking in a good 25% shorter than the first version.

Finally, there is the sextet of sylphs, No. 3 in 8 Scenes from Faust and part of Scene 7 in The Damnation of Faust. Which version is better? This case is a split decision if there ever was one. The 8 Scenes version is scored for six soloists taken from the chorus; the chorus itself, or at least a semichorus, is to sing the final version. By using the full chorus, the elder Berlioz risked sacrificing some of the clarity of articulation demanded by this fiendishly tricky piece; but it was arguably a worthwhile risk, since the chorus is better able to invest the whispery iterations of "De sites ravissants," etc., with a soothing murmur and a suggestion of insect-like buzzing. Plus, in rewriting the sextet, the more mature composer brought greater economy to bear. The piece becomes more tightly constructed, clocking in a good 25% shorter than the first version.On the other hand, some of the alterations are no improvement. Though recognizable as a version of the same piece, the later version needlessly alters and/or dispenses with perfectly serviceable passages from the original sextet. Listen to both pieces side-by-side, and you will very likely spot bits from each that you prefer over their counterparts in the other. I particularly liked the chromatically descending lines toward the end of the sextet in 8 Scenes, which suggested to my mind the dripping of a drugged nectar onto Faust's slumbering lips. I also find it fascinating to compare the different settings of the faster section ("Là, de chants d'allégresse," etc.), in a major key in the 1826 version and in a minor key in the 1846 version. Both pieces are wonderful to witness, and I grieve for some of the 8 Scenes touches that didn't make it into the Damnation version, but overall I think this is one piece that did benefit from the attentions of the hoary head.

Which is better: 8 Scenes from Faust or The Damnation of Faust? It's a complex question. Without the one, we would not have the other. In many ways, I feel the original pieces from 8 Scenes surpass their later incarnation in Damnation. But in revisiting his youthful pieces, Berlioz did tighten them up and intelligently integrated them into an larger dramatic structure. And all that goes without even mentioning the numerous additional numbers, many of them for the chorus, with which he rounded out the later work.

Which is better: 8 Scenes from Faust or The Damnation of Faust? It's a complex question. Without the one, we would not have the other. In many ways, I feel the original pieces from 8 Scenes surpass their later incarnation in Damnation. But in revisiting his youthful pieces, Berlioz did tighten them up and intelligently integrated them into an larger dramatic structure. And all that goes without even mentioning the numerous additional numbers, many of them for the chorus, with which he rounded out the later work.I have made it through few waking hours during the past weeks without thinking of the drinkers' chorus from the top of Scene 6. I can't help but snicker impiously at the wry "Amen" fugue improvised by the same drinkers after Brander's song. And near the end of the "dramatic legend," we visit hell and heaven in that order, experiencing Pandemonium (complete with incomprehensible lyrics sung to a devilish anthem and a demonic waltz) as well as the apotheosis of Marguerite (with the choir of angels ending the whole work by singing, "Come! Come!"). But I'm getting ahead of myself. You'll hear more about all that in a few days.

No comments:

Post a Comment