by Frédéric Chopin

Recommended Ages: 14+

The Polish-born Chopin (1810-1849) was a fixture of the Parisian cultural scene. He specialized in performing at the piano for small private audiences or small public gatherings. Other than two concertos, a few pieces for piano and orchestra, a couple works for cello and piano, some Polish songs, and a piece for flute and piano, he wrote almost exclusively for piano solo. His writing broke new ground in the world of Romantic music, with regard to harmony, the treatment of dissonance, the blurring of tonality, and the blending of ethnic and folk elements with forms and stylings of high artistic culture. He wrote several large-scale works for piano, including three Sonatas, four tremendous Ballades, an album of 24 Preludes, and two sets of 12 Études. Other single-movement pieces that he wrote may now be found collected in albums according to their respective forms or designations, such as Waltzes, Polonaises, Nocturnes, Impromptus, Rondos, Scherzos, etc.; though during Chopin's life, and even posthumously, many of these pieces were published either as separate opus numbers, or in groupings of two or three. Such is the case with Chopin's Mazurkas, as we will see below.

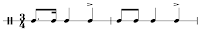

The Mazurka is a lively Polish dance in 3/4 time. It has a characteristic rhythmic pattern, illustrated here; though as Chopin proves, this can be varied to some degree without obliterating the sense of "mazurkaness." Chopin wrote tons of these pieces—as many as 58 of them have been published, and several more are believed to exist—covering a wide variety of moods and textures. In general these are brief pieces in a 3-part, A-B-A' form. The melodies often express a certain melancholy passion, but their range of moods runs from joyful triumph all the way to bitter despair. The left-hand part is often a type of "oom-pah-pah" pattern, though Chopin's incorporated more-than-traditionally sophisticated harmonies. And the significance of these pieces, as expressions of Polish nationalistic feeling, are a mark of the spirit of their time when many composers were importing folk elements (rhythms, scales, turns of melody, etc.) from their respective nationalities (Danish, Czech, Russian, etc.) into the traditionally French/German/Italian order of musical art. For all Wagner's ridicule of Chopin as a composer for the right hand, Chopin's Mazurkas demand nimbleness and sensitive expression in both hands, forcing the pianist to improve his technique without being out of the reach of a fair-to-middling note reader.

To be able to play all 58 of Chopin's extant Mazurkas, I would advise you to invest in an Urtext edition. But I must confess that I've been making do, lo these many years, with a cheapo Dover edition that only includes the 51 "numbered" Mazurkas, in numerical order. These include the Mazurkas that were published with opus numbers, including a couple of posthumous opus numbers, plus two Mazurkas that were published separately during Chopin's lifetime. So this run-down of Chopin's Mazurkas will only include the ones numbered 1-51—though, for the most part, I'm going to ignore this numbering and stick to "Op. x, No. y," a much more reliable method of keeping the pieces straight. For now, I don't have any plans to change editions. Urtexts are expensive and, for my purposes, the Dover (edited by Carl Mikuli) has been sufficient. And now, in brief, Chopin's Mazurkas...

Op. 6—4 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in F-sharp minor (3 sharps)

This piece is in something like a rondo form, with an opening refrain that returns after each of two contrasting episodes. First the melancholy refrain, notable for a triplet-eighth pattern that sometimes displaces the mazurka's dotted rhythm onto beat 2, is repeated in full. Then there's a passionate episode in the dominant1 key of C-sharp, punctuated by loud C-sharp octaves, and rounded off by a return to the refrain; this section is also repeated. The second episode features an anxious-sounding theme with lots of twitchy little grace-notes; then the piece concludes with a final return of the refrain.No. 2 in C-sharp minor (4 sharps)

This piece opens with an eight-bar introduction in which the melody is embedded in the middle of a dominant drone, like a hurdy-gurdy tune. The refrain, eight bars of chromatically-colored melody with a lively mazurka rhythm, is immediately repeated. Episode 1 (a jaunty little tune in the dominant key of G-sharp), together with the return of the refrain, is also repeated. Then we get Episode 2, a brighter and more expansive ditty in A major, modulating2 to G-sharp again, and bringing back the introductory passage before a double statement of the refrain (slightly varied the second time) closes the piece.No. 3 in E major (4 sharps)

Again, this piece has an introductory idea in which the left-hand plays open fifths (initially E-B) and the right-hand crosses over to play a descending riff in a deep bass register. The bright, jaunty main melody is based on a broken E-major chord; it ends with the introductory riff transposed up to B major, the dominant, and is immediately repeated. A majestic episode, also repeated, works its way back to the tonic. The music proceeds through another pageful of contrasting ideas before bringing back the introduction again, only now in A major. This heralds the return of the refrain, which on its second repetition is modified to form a brief, gentle coda.No. 4 in E-flat minor (6 flats)

After the longest piece in this group (No. 3 ran for 3 pages) comes the shortest, only one page long. Quick, simple, direct, it has the rounded binary structure3 characteristic of classical minuets and the like. The only innovative thing about it is the use of chromaticism to color the harmonies and to shape the direction of the melody. Plus, there is something cool about the way one of the inner voices shares the burden of the melody with the topmost voice of this delicately textured miniature.

Op. 7—5 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in B-flat major (2 flats)

Chopin has returned to his usual Mazurka proportions (2 pages) with a piece whose first move is to take off like a rocket. On its way back down it hits what may sound like "wrong" notes, but their wrongness is what is so right about this piece. The refrain returns as expected, though with some added decorations, after each of two refrains: a carefree one in F, and a strange, exotic-sounding, perhaps Central-Asian influenced second episode over a G-flat drone.No. 2 in A minor (no sharps or flats)

This ABA-form piece is the epitome of the type of up-tempo melancholy that seems to be a default setting in the Mazurka. There is something especially unsettling about the lack of a firm bass note on beat 1 of each measure, the chromatically downward-slipping harmonies, and even the central B section, whose relatively sunny, A major tinted surface covers an inward sense of being trapped in an endless cycle. At the heart of this aimless meander is a passage in F-sharp minor given to explosions of violent frustration. Chopin saves space by writing Da Capo al Fine4 at the end of the B section, rather than writing out the return of section A.No. 3 in F minor (4 flats)

This 3-pager is another instance of Chopin opening with a deep, dark, portentous introduction. The main theme has a touch of tragic melodrama in it. Though several distinct episodes follow it, this theme is not heard again until the end of the piece. The first episode leads from F minor to the cheerful relative key of A-flat major. Here Chopin uses the notation stretto5 in an atypical sense, meaning "a slightly faster tempo." Episode 2, following without a break, is in a triumphant D-flat major; then there's a sort of "cello" episode in E-flat minor, with the melody in the left-hand part and the right hand providing chordal accompaniment. After a souped-up repeat of the introduction, the main theme returns, dovetailing into a gentle coda.No. 4 in A-flat major (4 flats)

This charming, rondo-like piece has two episodes, the first of which is repeated along with the return of the refrain after it. The piece, though generally of a bright and genial character, revels in chromaticism, including (at the end of Episode 2) a whisper of the rather remote key of D major.No. 5 in C major (no sharps or flats)

Again the set concludes with a dinky little one-page piece, though it could also be the longest Mazurka of all. Why? Because it ends with the notation Dal Segno senza Fine6, which means that everything except the four-bar introduction is to be repeated over and over, world without end. The pianist who obeys all markings to the letter had better avoid this piece, because to play it as marked would be a sort of damnation, accompanied by music of rather slight merit.

Op. 17—4 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in B-flat major

The A section of this piece is one of the few "Type A Personalities" to grace Chopin's Mazurka Album. Virile and joyful, albeit touched with chromaticism, it contrasts charmingly with a playfully skirlinig E-flat major B section. This was one of the first mazurkas by Chopin that I played, and it remains a favorite to this day.No. 2 in E minor (1 sharp)

This piece opens with a threat of insufferable sentimentality that, fortunately, it does not fulfill. Instead, its A section ascends to a high register with music of exquisite feeling. As in many other instances, the B section has a touch of drone bass in it, but this also is relieved by something more dramatic and interesting.No. 3 in A-flat major

Something about the main theme of this A-B-A structure makes me think of those restless nights when one is too tired to read and yet too restless to sleep. The A section has a secondary theme in B-flat minor that adds some exotic touches, yet keeps the same sense of anxious thoughts turning in tight circles. Section B's main theme, in E major, is more expansive, perhaps the most enjoyable music in the piece; it too, however, has a rather pointless secondary theme, sort of a scale study in B major.No. 4 in A minor

Chopin breaks the pattern of his previous sets of Mazurkas by concluding this one with a longer-than-usual (four page) masterpiece, one that makes technical demands on the pianist above the norm for this album. For example, there are several runs of 15 eighth-notes that are supposed to be played over the accompaniment of a steady(ish) pulse of three quarter-notes. Have you been practicing your quintuplets, Kevin? Be sure to drill your chromatic scales, while you're at it. But it will be worth the extra homework, because this piece is such a heartbreakingly beautiful example of Chopin's genius. Slow, expressive, colored by more of those down-sliding harmonies, it tells a story that seems to come straight out of the heart. It's a compendium of romantic-era keyboard embellishments. Its middle section in A major challenges you to play two rhythmically independent voices with the same hand. And instead of bringing back the full A section, Chopin truncates it and adds a killer coda, concluding with a repeat of the hauntingly inconclusive introduction.

Op. 24—4 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in G minor (2 flats)

This piece opens with another one of the more famous melodies in the album, a tune both noble and mournful, full of nationalistic yearning. It's a simple piece with two episodes, one in F major and and the other in E-flat major, each complimenting the mood of the refrain.No. 2 in C major

Demure innocence is the character I would ascribe to this four-page piece. It remains bright even through its contrasting episodes in F and D-flat. The piece also features an oscillating introductory pattern that returns at the end, and a long transition back to the last refrain that may really be the emotional heart of the piece.No. 3 in A-flat major

This little number is downright perky, as Chopin Mazurkas go. Like several before it and more to come, it makes interesting use of hemiola7 and chromatically rich sequences.8No. 4 in B-flat minor (5 flats)

By contrast with the previous pieces in this set, this one is rich and strange, full of daringly original harmonies and textures. It begins with a striking introduction in which the right hand plays two voices edging closer together by alternating chromatic steps. Then comes a darkly exotic dance with two melodic voices on top of the accompaniment; the middle voice becomes increasingly active on each return of the refrain. One of the episodes is whimsical and jaunty; another introduces a mournful theme in bare octaves. Melody after melody unfolds in rich profusion, and the last half of page 4 is coda that dies away with heartstring-tugging soulfulness.

Op. 30—4 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in C minor (3 flats)

Graceful, almost delicate perhaps, this piece is one of several in this album that could serve as a typical example of a Chopin Mazurka. So maybe that's a nice way of saying there isn't much special about it. But it is written to the same standard of artistry and craftsmanship as everything in this book, so don't sniff at it.No. 2 in B minor (2 sharps)

Here is another Mazurka of the type that eschews the usual dotted-eighth rhythm, often employing triplet-eighths instead. The first episode is remarkable for its depiction of one doggedly climbing upward. Immediately following it is another episode in which the same two bars of melody is repeated over and over, taking a variety of meanings from the changing harmonies beneath it.No. 3 in D-flat major (5 flats)

The main theme in this piece considers a musical "To be or not to be?" as it dithers back and forth between major and minor versions of the same phrase-ending. It also has one of the more challenging left-hand parts so far in the book. The first episode is in the key of C-flat major that you thought I kidding about in my post on how many keys there are. See? It's a strong, middling-long (3-page) piece with some very assertive passages and an unusually strong ending.No. 4 in C-sharp minor

Pianists with small hands will have to compensate by rolling the widely-spaced left-hand chords in this piece. Not that the right-hand part lacks its share of fingering challenges, including some decorative flourishes. One gets the impression this was one of Chopin's favorite keys, from the amount of good material he gives it in this album—including this 5-page piece. It's comparatively hard, but it's full of richness.

Op. 33—4 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in G-sharp minor (5 sharps)

Here is another short, charming, relatively simple (ABA) piece that could be taken as a typical example of the form.No. 2 in D major (2 sharps)

Lightweight in touch but not in scale or expression, Chopin uses the major key to a touching effect in this 4-page piece. Part of what makes the main melody so endearing is the effect of hearing it repeated in the dominant key of A. The B-flat major episode adds a note of martial courage, while the transition back to D has an anxiously searching quality. The accelerating coda sinks in both pitch and volume while playing with an inner-voice variant of the main tune.No. 3 in C major

What lifts this piece above the level of the "typical example" is the unusual transition to the key of A-flat for the B section, quite distant from C major.No. 4 in B minor

A lot of pianists may come to consider this five-page piece one of their favorites in the album. The refrain's main theme expresses a feeling of nighttime loneliness and sighing, contrasting with a C-major second idea in which the right hand crosses below the left to play a "cello" melody. The passionate first episode flips around to the flat side of the tonal system, a sort of B-flat major tinged with minor-key inflections. After another refrain the first episode returns, immediately followed by the consoling gleam of B major in Episode 3. After entertaining a series of ideas in this key for almost two whole pages, Chopin uses an unaccompanied left-hand melody to make the transition back to the refrain, where the tension between B minor and C major prolongs the wistfully whispering ending.

Op. 41—4 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in C-sharp minor

The complex rhythms and harmonies of this piece combine with chromatic and modal effects in the melody to make this one of the stranger-sounding Mazurkas so far: majestic and yet uncertain, it only gradually reveals where it is going and what key it stands on. After four pages it climaxes with desolately crashing octaves, subsiding at last into a peaceful sense of arrival.No. 2 in E minor

There is something of a cry of anguish in the melody of this Mazurka as well, particularly when each repetition of the main melody ends in a passage of naked octaves. It's a good piece for learning to play chords that require your thumb to play two notes at one time. The B major middle section brings back the character of a drone with the melody in the middle, a texture we haven't seen for a few opus numbers.No. 3 in B major (5 sharps)

The rule for this piece seems to be irritating repetition relieved, now and then, by brief passages in octaves. It doesn't really get going, for my money, until almost Page 2, by which point it is halfway over. There are, however, some interesting harmonic twists and a very clear structure, which may make it a profitable piece for study and analysis.No. 4 in A-flat major

This piece sounds brighter, and therefore perhaps lighter (weight) than most in this book, almost like a piece of popular entertainment that accidentally got mixed up with a collection of art. But that impression is contradicted by the sophisticated way the central B section works its way to the distant key of C major and back again; to say nothing of the surprise ending in the middle of a reprise of Part B. At the opus-number level of context, it's like letting a novel end in mid-sentence: very whimsical and perhaps disturbing.

Op. 50—3 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in G major (1 sharp)

This piece is an example of Chopin in his spectacular mode. Episode 1 is a bit of exotica in E minor; following a repeat of the fanfare-like refrain is a cello melody in C minor. Episode 3 is G minor-ish but contrives to sound more remote and exotic. The coda exploits more of the major-minor ambiguity that Chopin so often uses.No. 2 in A-flat major

After an eight-bar intro, Chopin introduces a melody full of languid chromatics. The F-minor first episode contrasts so gently with the refrain that it almost sounds like a subsidiary idea, though it never returns; whereas the entire second episode, a jaunty passage in D-flat major, is repeated in two segments before the final return of the refrain.No. 3 in C-sharp minor

After two four-page Mazurkas, Chopin caps this opus number with a six-pager—ensuring that subscribers got their money's worth, no doubt! Though his C-sharp minor Mazurkas as a group are among my favorites, this one in particular stands out with its pleading theme, treated contrapuntally, followed by subsidiary themes in A major and G-sharp minor, rather like the subject groups of a sonata than episodes in a rondo or da capo form. The first real "episode" as such is a B major melody that cycles repetitively over a variety of harmonies, relieved by a contrasting central section of its own. Then all three themes of the first section come back, leading finally to an amazing two-page coda based on the first theme. After traveling vast tonal distances rich in harmonic scenery, the piece dies away slowly and gently except for a few loud, final octaves. The day I first played through this piece, I felt I had made an awesome discovery.

Op. 56—3 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in B major

A cello melody opens this piece, sequencing through a series of keys before finding its way to G major by measure 6; only in bar 16 does Chopin strongly assert the home key of B. This tentative searching and triumphant arrival are the main contrast of this piece, in spite of Episode 1's burbling stream of E-flat major melody. Episode 2 is the same material as Episode 1, only transposed to D major; this, together with a sort of "development-cum-coda" added to the third repeat of the refrain, suggests again a variant of sonata form. It also has one of the stronger endings in the album.No. 2 in C major

There is something exotically Eastern about the chromatic inflections and melodic repetitions, combined with dronelike ostinato, of the main idea in this piece. Again Chopin provides contrast with a cello-tune episode, this time in the relative key of A minor. Several other contrasting ideas, all similarly tinged with ethnic hues, cross the stage without a break before the A section returns.No. 3 in C minor

This is the piece that brings out the importance of holding a tied-over note in the middle voice while both hands play several bars of music for the outer voices. The result is one of the most interesting and effective of Chopin's Mazurka themes, part of a refrain that comprises several distinct ideas, all of which are repeated before he begins introducing contrasting sections. Without describing the other themes in detail, let me simply say they are equally effective and show their author in command of a wealth of inspiration. And again, the depth and breadth of six pages of marvelous music give a satisfying ending to a small opus number.

Op. 59—3 Mazurkas:

No. 1 in A minor

As increasingly happens as this book progresses, we find in this piece another melody that everybody who has played or listened to a quantity of piano music should know. The whole first page is a fully-formed musical period, headlined by a tune that at times droops with despair, and then aspires upwards with urgency. The first episode searches anxiously through several "sharp side" tonal areas before coming back to the refrain on page 3. then the piece explores the "flat side" with a momentary sideways slip into E-flat major, which Chopin humorously treats as an uncorrected mistake before returning home to A minor for a musing, and perhaps amusing, coda.No. 2 in A-flat major

Starts out promising little more than mellow, major-key sentimentality. Then Chopin slathers on an extra layer of chromatic richness, along with a melodically active middle voice. After an episode that, in a way peculiar to Chopin, delays resolving harmonically to the expected tonic chord, the refrain returns in a cello variation, then in a coda that builds harmonic and dramatic interest until a chromatic run of eighth-notes near the end.No. 3 in F-sharp minor

The dark anxious agitation of this piece is (one imagines) like that of a rainy Warsaw afternoon, full of descending sequences that somehow suggest a certain fussy repetitive business, akin to OCD. A brief A major episode sheds a ray of sunlight into the murk. The longer second episode in F-sharp major is full of jumps and flourishes, like a wet bird trying to shake its feathers dry enough to take off. The feeling of obsessiveness creeps in again at the end of this episode, then calms down during the transition back to F-sharp minor for the refrain. The five-page piece ends in a longish coda (more than a page) rich in textural and harmonic developments, comparable to op. 50 no. 3.

Op. 63—3 Mazurkas, the last to be published in Chopin's lifetime:

No. 1 in B major

I just made the acquaintance of this piece as I was preparing to write this. Lovely! I don't know how I've missed it, except—as you may have noticed—there are a lot of pieces in this album! With a lot of wide-spread chords in the left-hand part, it comes across with a kind of strumming, guitar-like effect. That and its relatively sunny disposition, full of masculine verve, make one think of holidays in Spain. The B section is a bit lighter and gentler, in A major. At four pages in length, this is the only piece in this opus number longer than two pages.No. 2 in F minor

The first note of this tune is a dissonant "wrong note," triply emphasized by its length, rhythmic placing, and dynamic markings. It comes across as a scream of anguish, dominating everything else in the A section. The atmosphere lightens somewhat in the B section, though the tonal contrast to the relative key of A-flat major is no more than one would expect. Chopin's chief objective in this piece seems to be re-educating us about the use of dissonance—a task he accomplishes with the first note of the right-hand part, and each repetition thereof.No. 3 in C-sharp minor

This little group ends with a melancholy little number so graceful that it could almost pass as a waltz; the classic Mazurka rhythm doesn't appear until measure 19. Its phrasing also reminds me of "December" in Tchaikovsky's Seasons, though Chopin uses chromaticism differently. The B section in this ABA structure is in D-flat major, a key that on the page looks deceptively distant from C-sharp minor, though to the ear it is equivalent to C-sharp major. Did Chopin notate the key change this way simply because it is easier to read five flats than seven sharps? It doesn't seem in character for him to be afraid of fistfuls of accidentals; so I have to conclude that he was playing a psychological trick on the performer. Imagine the difference it might make in his interpretation of the piece!

Op. 67—4 Mazurkas, published posthumously in 1855:

No. 1 in G major

Like a previous G major Mazurka, this piece shows Chopin in his brilliant, lively register. The A section has a central idea leaning toward the dominant key of D; the B section, in C major, features a passage of hurdy-gurdy drone in the left-hand part. It comes to a very strong, assertive ending.No. 2 in G minor

Delicate, graceful, and touched by a sobbing gesture, the main melody of this piece is nevertheless too sweet to be considered really tragic. It's more like having a good cry, relieved by a smile of B-flat major in its B section. The most touching part is probably the unaccompanied phrase of melody that makes the transition back to the A section for a last, indulgent sniffle.No. 3 in C major

This is one of the most simple, straightforward pieces in the album, with an intuitively satisfying melody touched by a sense of wit and the appeal of a popular lyric. The very brief B section suggests D major as the secondary tonal area, but it more or less vamps until section A is ready to return.No. 4 in A minor

Though no longer than any of the other pieces in this opus number (two pages each!), this Mazurka has a depth of focus and richness of color absent in the others. It suggests perhaps that Chopin's publisher chose arbitrarily from manuscripts left behind by the late master, and that this is the only one of the four that really represents Chopin at his maturest. Adding a bit more weight to it (at least superficially) are the repeat signs that, in effect, make it almost half-again longer than each of the other pieces in this opus. The middle segment is in the parallel key of A major, but this slight tonal contrast takes nothing away from the sense that Chopin is opening a view deep into his complex character.

Op. 68—4 Mazurkas, also published in 1855:

No. 1 in C major

This is a charming, bright, lively piece, full of popular appeal. I would place it on a level similar to some of Scott Joplin's piano rags (which may be featured on this thread someday). But again, I don't think it represents the most mature side of Chopin as a creative artist. The chromatic touches seem superficially stylish, rather than expressing complex and contradictory feelings. The F major middle section strikes me especially as thin stuff—though as I say, always charming.No. 2 in A minor

This piece illustrates that my problem with No. 1 of this opus was not simply an artifact of being in the key of C major. Even in a minor key, this piece has less bottom in it—less creative dash and unconventionality—than most anything seen so far in the album. I mean, just look at the left-hand part; there is hardly an unexpected chord anywhere in it, all perfectly tonal and predictable. The touches of chromaticism in the right-hand part are (here's that adverb again) superficially exotic sounding, but no more than that. The A major central section, unlike that of op. 67 no. 4, really makes one feel we haven't gone anywhere much. The best that can be said of this piece is that its pianism is exquisite: the notes fall under the hands as if of themselves, and the instrument responds with attractive sonorities. But I'm not sure Chopin would have published this piece if he'd had any say in the decision.No. 3 in F major (1 flat)

Again this is a bland Mazurka, more the kind of piece that shows the flawlessness of Chopin's pianistic writing, and that perhaps more faithfully conveys an idea of what a traditional Mazurka might sound like, without having the composer's peculiar character imprinted on it. The B-flat major middle section skirls briefly in a high register over droning fifths, reminiscent of bagpipe music; I think this is also an artifact of an early attempt by Chopin to translate traditional Mazurka stylings into written piano music.No. 4 in F minor

Here is one piece in this opus worth working up enough moisture in your mouth to spit on it. Like one of the previous Mazurkas, it ends with a Dal segno senza Fine notation, making it possible (at least in concept) to repeat this piece in a perpetual loop, world without end, or until your piano strings lose their tension. Unlike that earlier chit of a piece, this one isn't mind-numbingly dull. In fact, it is so daringly chromatic that it almost obliterates one's sense of tonality. I hesitate to guess whether it represents an experiment at the end of Chopin's life, or a fit of youthful brashness before our Fred figured out how to load chromaticism into a Mazurka without unspringing the whole tonal system. Either way, it's interesting to play through once or twice in a row—challenging, elusive, and at times almost arbitrary sounding—and it was a foreshadowing of things that were to come.

And finally, two mazurkas published separately, without opus number:

Mazurka No. 50 in A minor, subtitled "Notre Temps"

This four-pager is more like it—more like Chopin in his prime, that is. A Chopin unafraid of stressing an augmented triad (beat 2 of bar 2). A Chopin who, even in his predictable moments, wrote like a virtuoso in command of the full range of the keyboard. A Chopin who could spice up a long melodic passage in bare octaves with a few off-beat and often dissonant chords. A Chopin with the confidence to write a dotted-eighth figure immediately followed by triplet eighths, and mean it. I like this piece. I wish I knew it better; but knowing that the "posthumous" end of the album was stocked with juvenilia of a lower standard of artistry, I have unjustly neglected it. It turns out this isn't a posthumous piece after all; it and the next piece were both published in 1841—even before opus 50!Mazurka No. 51 in A minor, dedicated to Émile Gaillard.

Again, I am chagrined to find that I have unjustly neglected this piece until now, perhaps confusing it with one of the "posthumous" A minor Mazurkas, of which I have so low an opinion. This may even be a more interesting piece than "Notre Temps," opening with a cello melody. Fellow Dover Edition cheapskates, watch out for a misprint in the left-hand part in the second measure of the B section (after the key change to A major), where the last eighth-note in the top line should be an F-sharp, not an E. The first tenor note in the fourth-to-last measure of the first A section may also be a misprint; I would be surprised if Chopin didn't mean for it to be an E. Again the middle section features a melody in ocaves, this time fully accompanied by the left hand. And though the numbering of the Mazurkas gives the false impression that this piece was Chopin's last word on the form, the coda of this four-page piece—featuring a right-hand trill for 10 bars, culminating in an acrobatic leap two octaves up—puts a magical "FINIS" on the last page of the album.

1In musical analysis, "dominant" means the fifth note of the scale, and the major triad built on it; in Roman-numeral notation, V. When the "tonic" (i) is F-sharp minor, the dominant key (V) is C-sharp major.

2i.e., changing key.

3i.e., the material from Section A comes back at the end of Section B, and both sections are repeated.

4literally, "From the top to the end." Fine ("end") is written at the end of the A section.

5literally, "tightening." In fugues, stretto designates overlapping entries of a fugue subject.

6literally, "From the symbol without end." The symbol in question looks like this. The more usual marking Dal Segno al Fine or al Coda means you go back to the point in the music where this glyph appears and play from there, either to the end (Fine) or to another marking that looks like a gun-sight, which means "skip from here to the Coda," a concluding passage similarly marked.

7i.e., alternating rhythmic groupings of 2 and 3.

8i.e., short melodic and harmonic patterns repeated at different pitch-levels.

No comments:

Post a Comment